Over the course of 2022, Cambridge Global Challenges mapped 7,416 publications co-authored by the University of Cambridge and researchers based in low- and lower-middle income countries (LIC/LMICs). Using the Dimensions analytics platform – a research database with over 135 million publications classified by machine learning – we have specifically mapped publications in peer reviewed, international journals. Why? In a word: equity.

The pursuit of equity in research partnerships is increasingly recognised as crucial for addressing the power imbalances characteristic of collaborations in recent decades. The mapping of research collaborations, especially between Global South and North researchers, can be a valuable tool for measuring a partnership’s extent. Of course, the co-production of research isn’t sufficient to guarantee a partnership is genuinely equitable. While we recognise the limitations of focusing solely on publications, mapping can nonetheless provide a useful basis for identifying the nature of engagement across countries and subject areas.

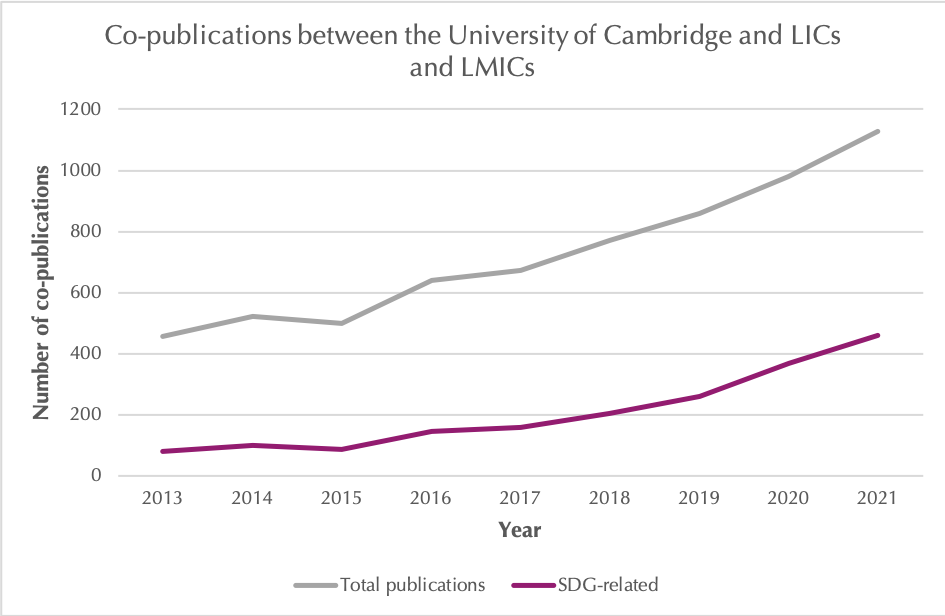

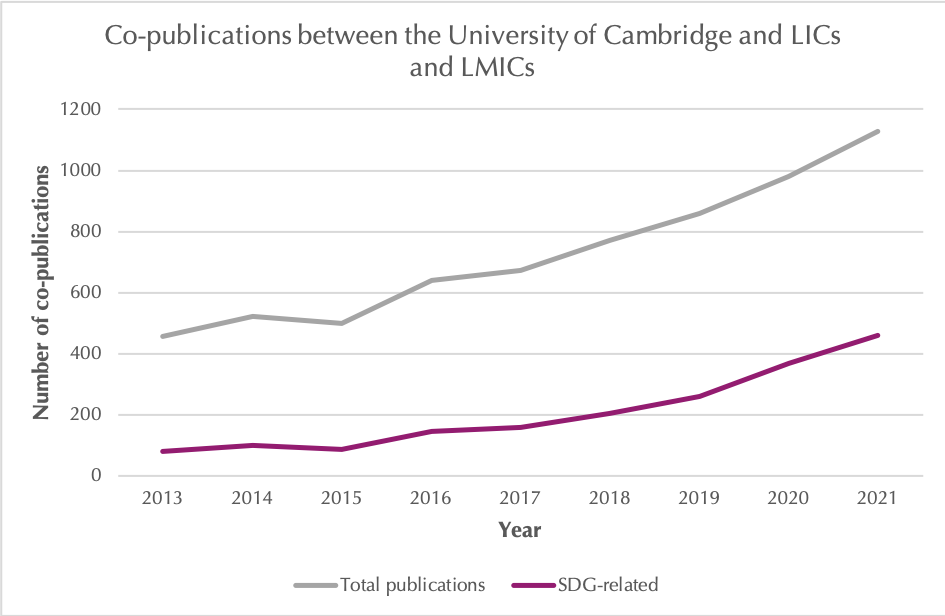

Figure 1 | Total number of publications between 2013 and 2021 which include at least one author from the University of Cambridge and LICs/LMICs (grey) or which are related to any of the UN SDGs (purple).

Figure 1 | Total number of publications between 2013 and 2021 which include at least one author from the University of Cambridge and LICs/LMICs (grey) or which are related to any of the UN SDGs (purple).

What does our analysis show?

We find that collaborative publications between the University of Cambridge and LICs/LMICs have consistently increased over the past decade, reaching more than 1,000 in 2021. Of these, over a quarter are related to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (see Fig.1); Dimensions assigns SDG tags to approximately 13 million publications, using a machine learning algorithm trained using almost 700 academic-reviewed keywords and phrases.

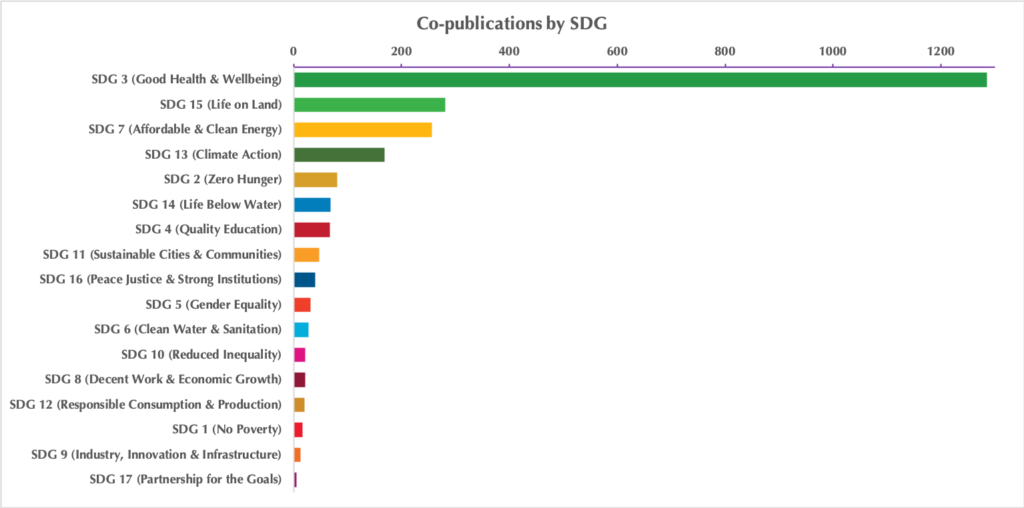

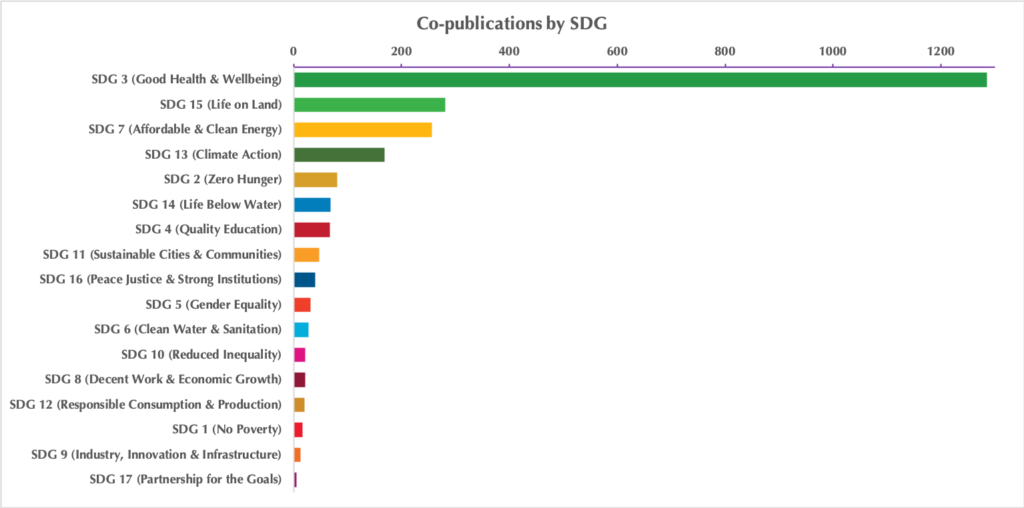

Our analysis reveals that the number of co-authored publications is highest by far for SDG 3 (Good Health & Wellbeing). This is followed by SDG 15 (Life on Land), SDG 7 (Affordable & Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) (Fig. 2). This suggests that LIC/LMICs have significant interest in the climate and health space, and are key partners in advancing the SDGs.

Figure 2 | Number of publications between 2013 and 2022 which include at least one author from the University of Cambridge and LICs/LMICs, which are related to each of the UN SDGs according to Dimensions categorisation.

Figure 2 | Number of publications between 2013 and 2022 which include at least one author from the University of Cambridge and LICs/LMICs, which are related to each of the UN SDGs according to Dimensions categorisation.

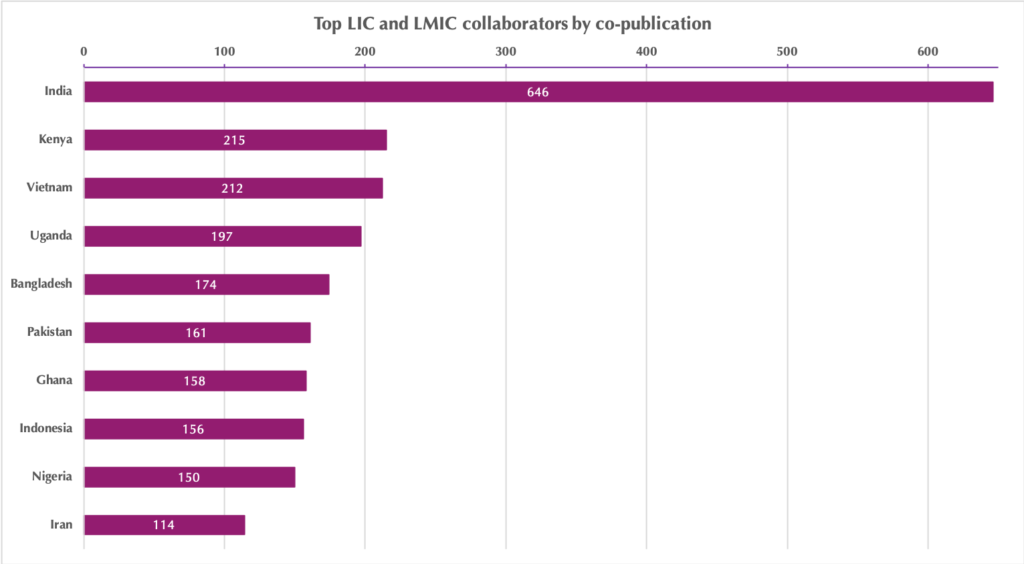

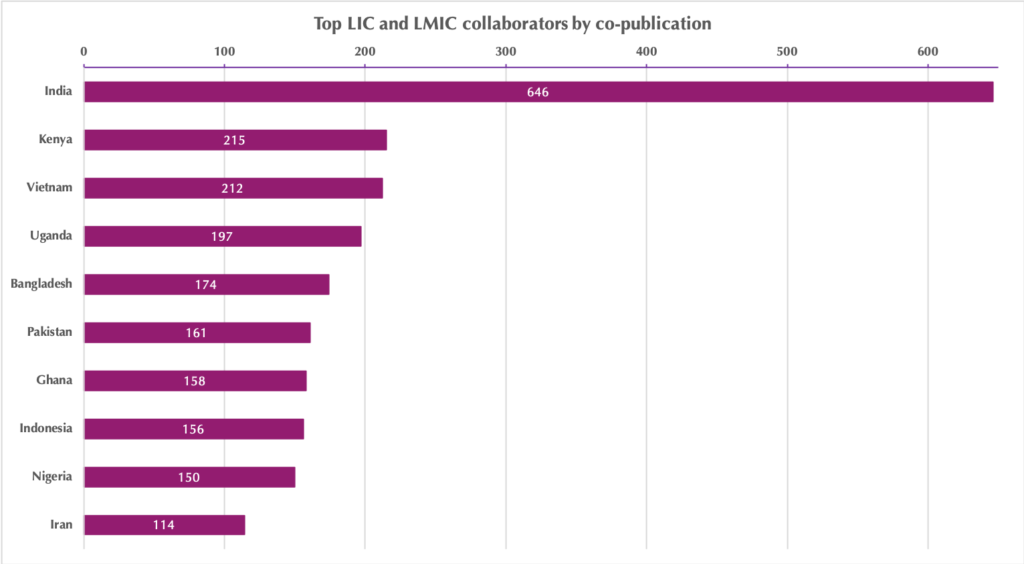

The ten countries with which the University of Cambridge has the most collaborations, as evidenced through co-publications, are primarily located in Africa and South or Southeast Asia, with India being foremost among these (Figure 3). Country collaborations vary considerably if we look at specific SDGs. For example, Ethiopia has strong representation in SDG 4 and the Philippines in SDG 15.

Insights on institutions

We’ve identified organisations and researchers in LICs/LMICs with whom Cambridge has strong publishing records. In many cases, all co-publications associated with an LIC/LMIC relating to a particular SDG are linked to just one or two institutions.For example, in Pakistan, Aga Khan University is associated with publications linked to SDG 3 (Good Health & Wellbeing) and SDG 6 (Clean Water & Sanitation), while COMSATS University Islamabad (CIIT) is associated with co-publications related to SDG 7 (Affordable & Clean Energy) and SDG 13 (Climate Action).

This data provides insight into centres of expertise at a global and in-country level. It also highlights potential future partners in LICs/LMICs. Understanding these trends could also help facilitate rapid coordinated responses to funding bids as well as other forms of engagement.

Figure 3 | Top ten LICs/LMICs with the highest number of co-publications between 2013 & 2022 with the University of Cambridge, which relate to the UN SDGs according to the Dimensions database.

Figure 3 | Top ten LICs/LMICs with the highest number of co-publications between 2013 & 2022 with the University of Cambridge, which relate to the UN SDGs according to the Dimensions database.

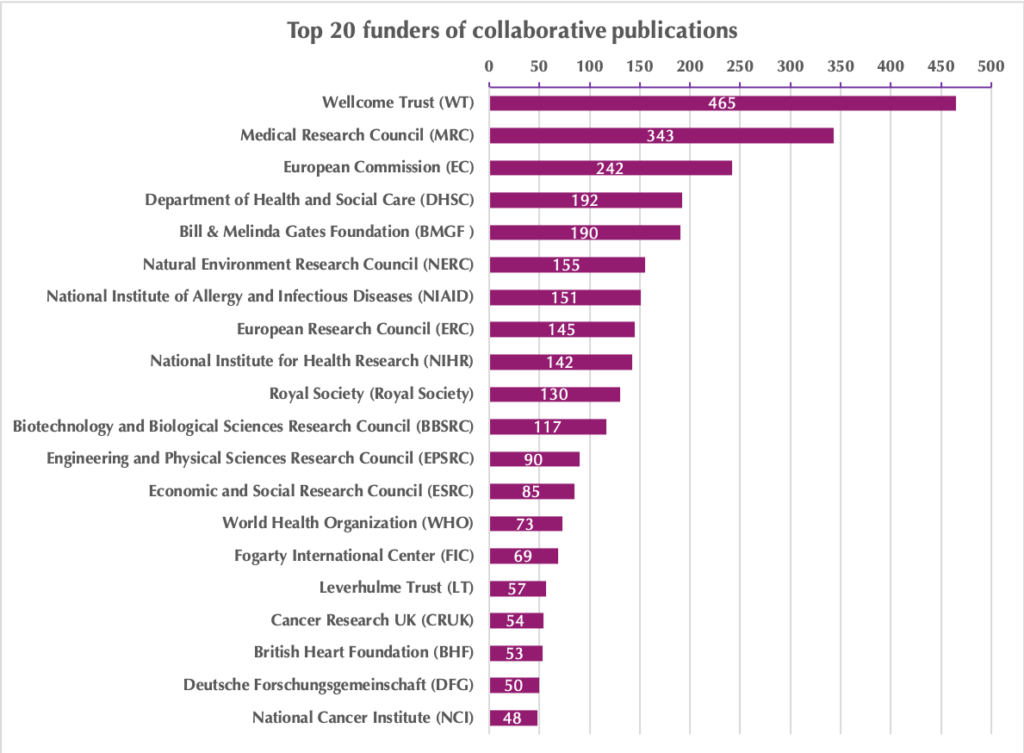

Insights on funding

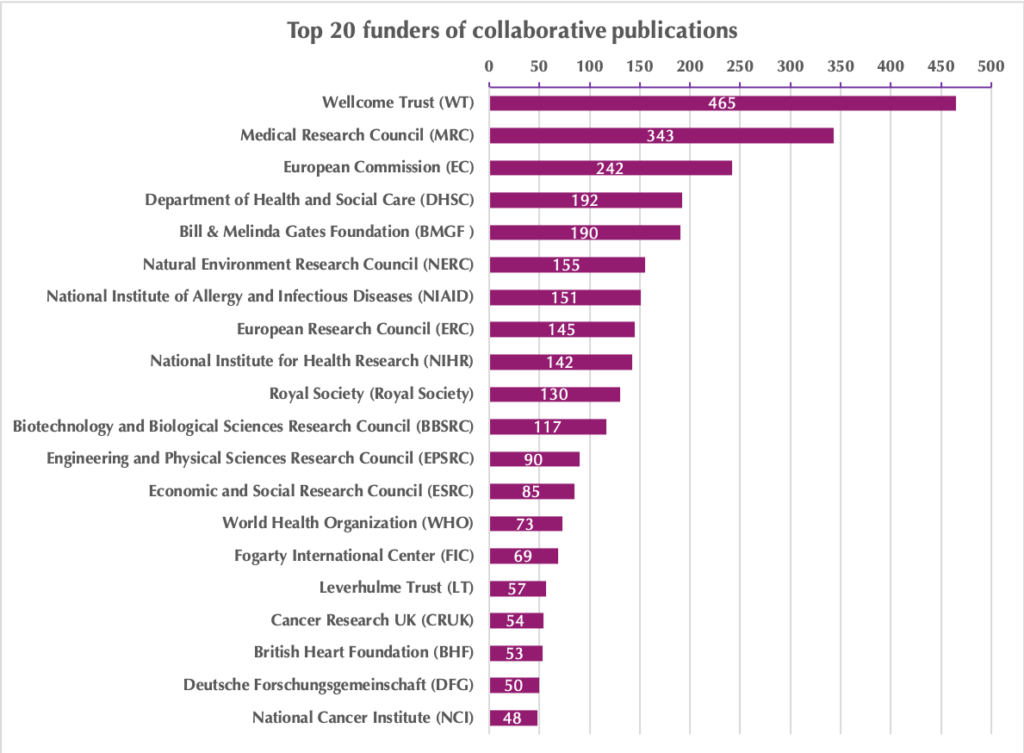

The Dimensions database also reveals valuable information regarding funding sources. While most funding for these publications comes from UK-based organisations, there’s also good representation of national agencies in other countries and philanthropic foundations (Fig. 4). It’s worth noting that many of these co-publications are not led by Cambridge researchers, but rather by international partners, including from LICs/LMICs.

Given the predominance of UK-funding in generating co-authored research, it is important that we understand how this might change in future. The UK research funding landscape is in a time of transition: large funding streams are winding down and uncertainty remains around association to Horizon Europe. At the same time, there is increased commitment by some funders to fund co-created research, and philanthropic funders are moving toward direct-funding models in LICs/LMICs. It will be important to observe how this funding landscape will evolve; will collaborations with LICs/LMICs suffer, or could opportunities arise that give greater opportunities for LICs/LMICs to take the lead?

Figure 4 | Funders associated with the highest number of co-publications between 2013 & 2022 according to the Dimensions database

Figure 4 | Funders associated with the highest number of co-publications between 2013 & 2022 according to the Dimensions database

Evaluating Dimensions

The co-production metric has proven itself useful for gathering information and drawing broad conclusions regarding international collaborations. However, it’s important to recognise the limitations of the Dimensions database. Country affiliation data for each publication isn’t always available, but a number of analyses indicate a year-on-year upward trend and shrinking of the coverage gap over time. Moreover, we have identified several instances where Dimensions lacks complete funder data. Funding sources aren’t always effectively linked to publications in the metadata gathered by Dimensions, resulting in some funders being unlisted, or their funding records underestimated.

Finally, in any discussion regarding equitable research, we must consider the equitability of the tools we’re using. While much of Dimension’s data is freely available, many of the analytical features which make it valuable for mapping are accessed through a subscription model. This includes the ability to filter by institution, funding sources, or country. Universities in LICs/LMICs often face significant funding constraints and as such may be disinclined to prioritise paying for Dimensions access. This engenders an inherent power imbalance between the University of Cambridge and institutions in the Global South, as we can access and deploy this information in the establishment of partnerships, while LIC/LMIC-based researchers may lack the same opportunity.

In short, Dimensions represents a valuable tool for understanding the research portfolios within higher education institutions and could help identify future partnerships that are both equitable and valuable. However, tools like Dimensions carry their own concerns when it comes to equitable practices.

Comments